The Vision of Adèle

I had always been an explorer in my heart. I read everything a young boy could read about adventurers, from Shackleton in Antarctica and South Georgia, to Heyerdahl and his Kon Tiki. The combination of scientific research and hands-on adventure that they provided appealed to me.

My previous sailing yacht, Swedish Caprice, an eighty foot sloop, was built at a small Swedish yard. Together, over more than fifteen years, we sailed around most parts of the globe, and I spent about three months a year aboard. We visited many of the places familiar to blue water cruising yachtsmen – the Pacific Islands from Micronesia to Tahiti; the Far East, from Timor in the south to Luzon in the north, Phuket in the west to Irian Jaya in the east. We saw Madagascar, the African Coast, the Seychelles and Maldives in the Indian Ocean, Alaska and Mexico and the classic cruising areas of the Caribbean and the Mediterranean. But, in time, I came to yearn to go further, to explore the wilder, more dangerous places where few yachts travel.

I started planning Adèle in 2000, but it would be five years before she was built and launched. She was to be a yacht that would explore high latitudes and low temperatures as well as being at home in the tropical seas. The archetype to do this is the motor explorer yacht, with high bow, reinforced hull and tenders placed amidships – but this wasn’t what I wanted. Exploring the seas should be intimately related to sailing, and a sailing yacht is about beauty, speed and adventure. Beauty is in the eye of the beholder, and to me it lies in the classic lines of yachts like the old Prince of Wales’s Britannia and Kaiser Wilhelm’s Meteor, or the America’s Cup yachts of the thirties – long overhangs, low freeboards, a flush deck and tall masts.

But could this be combined with a modern rig, modern engineering and a seaworthy hull? I didn’t know until I met Andre Hoek, the brilliant Dutch naval architect who shares my passion for photography, sailing and sailing yachts. Andre was a driving force in the creation of Adèle – while always being able to listen and to pick up ideas from his colleagues or from me.

Andre showed me his vision of a large superyacht constructed from the latest materials, filled with the latest technology – but built to classic lines. It was a far cry from the many superyachts that looked like motorsailers. I knew that this was exactly what I wanted. Adèle was to become the first Hoek superyacht, and she was to have several followers from his drawing board over time.

Adèle had to be longer than I had originally anticipated, to get the accommodation required, but she carries her classic heritage so gracefully, it was worth it.

When you are exploring, function is as important as form and she was meant to be fast, with a dreamy, easy motion through all but the roughest seaway. We tested the designs in both the Delft tank facility and the wind tunnel in Southampton., opting for a short fin keel with a heavy bulb because it was less vulnerable than a winged keel, which if damaged would be impossible to repair in far away waters.

The ketch configuration was chosen to give Adèle more possible sail combinations, making it easier to balance her in all conditions. And it allowed for a much safer sail plan in big seas – with just mizzen and headsails set she could sail downwind in the roughest weather with no danger of dragging the main boom and causing a potentially catastrophic broach. When the wind dropped, full mainsail and mizzen staysail would produce an enviable amount of horsepower for Adèle to glide along in the lightest of airs with her easily driven hull. And if all that were not enough, a sloop design would have necessitated a single mast so tall that it could not pass under the Bridge of the Americas over the Panama Canal.

Other decisions were just as practical – we fitted mechanical steering. In the modern era, Adèle was probably the largest yacht so equipped, but it is a big contribution to safety in out-of-the-way places. It gives a true feeling of her motion in the sea when you have Adèle’s reaction through her rudder back to your hands. For similar reasons, we shied away from in-boom furling, because the consequences of a failure would be disastrous far from big yards and sailmakers. Instead, we chose old-fashioned and seaman-like reefs, but with both reefline and halyard on synchronised captive winches to make it easy to shorten sail. And again, it wasn’t only safety concerns that dictated this, but also the fact that a traditionally reefed mainsail or mizzen stands better and makes it possible to sail higher – closer to windward – and faster.

From Concept to Launch

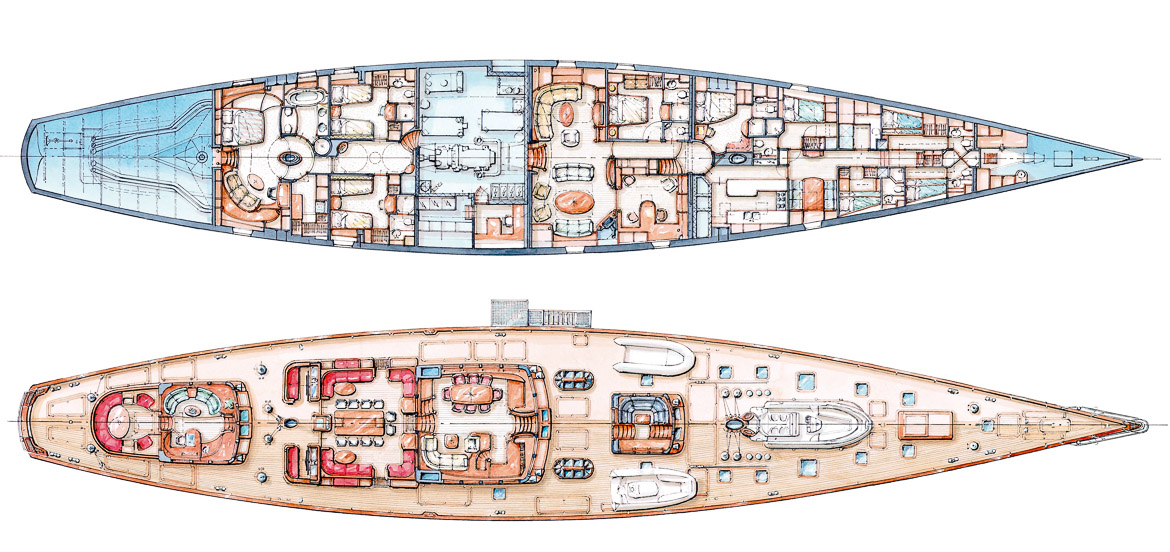

It took several years of hard work by a team of naval architects and designers from Hoek Design and other consultants, to move from a simple vision to the thousands of drawings that are necessary to build a large yacht. Adèle grew in size in the process – originally 173 feet and ending up at 180 feet. Andre and I travelled around to meet yacht owners, captains, crew and builders at different yards to get comments, advice and criticism of the plans. Using their valuable help and experience we modified several aspects of Adèle, particularly the interior. For instance, and perhaps understandably, neither Andre nor I had fully understood the importance of the size of the laundry room area. I’m happy that we extended that – now that I know that we ran the two washing machines for around ten hours a day, every day (with the exception of stormy weather at sea) during our two years of exploring.

Vitters yard in northern Holland converted the hull to the finished product, and a year and a half later – exactly on time and as planned – she was ready. It was time for a party. Adèle was the biggest yacht Vitters had built, a step into the unknown for Andre Hoek, and both had emerged triumphant.

Adèle was put on a barge heading for her new and natural home – the ocean. The keel was fitted, the masts stepped, the sea trials commenced and the crew moved aboard. It was a spring launch ahead of those sea trials, a new birth for the summer – but like any adored new born, she would have to get a little older and get some life under her keel before she could be christened.

Sailing Adèle

Adèle is a powerful yacht and carries a large sail area both upwind and downwind which, together with her narrow hull, gives her an impressive speed even in light air.

Her ketch rig is more versatile than a sloop allowing for a wide range of sail combinations that can be controlled safely in heavy weather. Her mainmast is as tall as possible whilst still allowing passage beneath the Bridge of the Americas in the Panama Canal. Including antennae, the tip is 63.6 metres above the waterline.

Using computer models and wind tunnel testing, Adèle was designed to be sailed with all sails set (genoa or yankee, staysail, main and mizzen), a total sail area of more than 1,500 m2. Sailing close-hauled the staysail doesn’t contribute that much, but neither does it create drag. In smooth water she sails close-hauled at an apparent wind angle of around 25 degrees, but in rough conditions with large waves that can increase to 35 degrees.

On a beat into the wind we would reduce sail at around 15 knots of wind speed, starting with a reef in the genoa and then in the main and mizzen. Reaching in light winds (6 to 12 knots) Adèle slices through the water about a knot faster than the true wind speed and this can, in good conditions, increase to two knots faster than true wind speed. As the wind creeps further aft the apparent wind is reduced so the mizzen staysail can be set. Designed as a reaching sail and therefore relatively flat, it substantially improves per-formance in light air and is easy to set, trim and furl. Ideal angles are between 60 and 120 degrees apparent.

Just like no sailing yacht can sail straight into the wind, neither does Adèle sail straight downwind. Adèle’s speed means that she generates her own wind (assuming the true wind isn’t coming from straight behind) and we would normally be more efficient sailing at a downwind angle of a maximum of 130 degrees to the wind. Conversely, that means that we have to gybe downwind as well as tack upwind, and our sailed distance increases.

Adèle’s spinnaker is asymmetric and designed, like most modern fast and large sailing yachts, to be carried without a spinnaker pole. At 1,500 m2 it was certainly one of the largest spinnakers ever made (and probably still is), and the expanse of red and white sail cloth is a fantastic sight. But I have to admit that it is a handful to hoist, sheet and take down! Used in moderate conditions, together with the mizzen staysail on a beam or broad reach, Adèle sports an impressive 2,700 m2 of canvas.

Reefing

The main and mizzen are furled via traditional slab reefing systems with ‘Park Avenue’ booms (very wide booms), lazy jacks from boom to mast and full length battens in both sails. The main boom is 18m long and 1.35m wide.

The first design was based on in-boom furling for the main and mizzen, but the decision was taken that as Adèle would be sailing in remote areas, a reefing system that would require a minimum amount of maintenance on the sails would be preferable.

The lazy jacks and full-length battens give much better control of the sail, and of course the mainsail has a better profile giving higher upwind speed. To simplify reefing we instead developed a reefing sys-tem where the first reef is taken on a captive winch that is synchronized with the (also captive) halyard winch. Although it works like a push-button automated reefing system, nothing replaces the vigilance of the crew.

Sailing upwind we take in a reef in the main by staying close-hauled and letting out the main boom, while the foresails and mizzen continue to work. That is one of the advantages with two masts. The process is then repeated the other way, when we take in a reef in the mizzen.

Both the main and mizzen are stowed on the booms by the help of a car system on the mast, where every second car goes to port, with the following one to starboard, helping the process of folding the sails and reducing the stacks of the cars (which is of considerable height anyway).

After the main or mizzen is hoisted, the top of the sails are locked in position by special locks on the masts that take all the tension. The halyard winch can then be released and the pressure on the mast is reduced. Cunningham, outhaul and boom-vang are adjusted hydraulically to assure optimal shape of the sail in all conditions.

The genoa and forestaysail are both carried on Rondal hydraulic furlers, and the sails are strength-ened at the natural reefing points (see table). In heavy weather the sails are reduced in several steps depend-ing upon the weather conditions, the sea and the wind angle.

The staysail and genoa are hoisted with the halyards taken to any of the mainmast winches. The halyards can then be tensioned by a hydraulic ram for each sail, placed at the mast.

In storm conditions, Adèle is designed to carry a reefed mizzen and staysail. During the crossing to Cape Horn we found that downwind we benefited from having only the mizzen and headsails hoisted, because heavy seas can induce a rolling, where the main boom could dig into the water with very negative consequences. On my previous yacht, an 80 foot sloop, we lost two booms that way. On Adèle, we take down the main in those conditions and sail safely with mizzen and genoa. We can still do more than 12 knots even in moderate winds.

Rig and winches

The masts and booms are made of carbon fibre. All standing rigging was stainless steel rod. A carbon fibre spar is carried at the forward end of the main mast for hoisting and lowering the large tender.

We have a crow’s nest with seating for two persons on the main mast, which can be hoisted and lowered via a hydraulic captive winch controlled from deck or from the crow’s nest itself. It goes to just below the inner forestay (~40 m above the waterline).

The spreaders are angled backwards. That means that in normal conditions we don’t have to set the running backstays, but we always set them on ocean crossings, in rough conditions or when motoring.

Adèle had 12 hydraulic captive winches (where the line automatically is rolled up on the winch drum) and 10 hydraulic normal winches plus a couple of snub winches. Adèle also has two anchor winches forward and one for the stern anchor aft.

All upwind sails are sheeted to captive winches. The mizzen staysail is sheeted through the mizzen boom and back to a winch at the mizzen mast. The spinnaker is sheeted to the big primary winches placed either side of the mizzen mast. Those winches also handle the running backstays. They back-wind to pay out the sheet (or running backstay) safely, and can also be used as back-up winches for the yankee, if the captive winches should fail. This never happened to us, and the forces are so strong that we would have to be very cautious using them.

Living Aboard Adèle

Deck

Adèle’s sheer size allows for elegant lines and low freeboard, as well as living spaces that are big enough for a large group of guests on deck or in her comfort-able interior.

The deck is the focus of living on Adèle. Not just the place from where she is sailed, it is also an area to watch the world go by, an area to sit and read, eat or drink. It turned out that even in Svalbard and the Antarctic we had most of our breakfasts and lunches in the cockpit, although our dinners were below in the deck house.

The main cockpit is the focal point for sailing and socialising and can comfortably embrace forty or so guests. The fixed bimini overhead has windows for viewing the mainsail from the helm, and side windows can be rolled down in foul weather. There are four,

L-shaped sofas around the edge, and twin tables just forward of the helm stations. These are ideal for coffee, or a meal for just a few friends, and, combined with a central table that seats ten and is popular for dinner, it is a very adaptable area.

There is a natural inclination for everyone to look at the central electronic chart console between the wheels. Along with the digital instruments showing speed, course and wind, it enables captain, crew, owner and guests to follow the progress, and leads to much discussion.

Just aft of the side entrances to this cockpit are a pair of outboard-facing benches (where Lasse and I spent much time watching albatrosses in the far South Seas). There are also seats in the pushpit, large enough for two to sit for a cosy chat. Combined with benches in front of both the main and aft deck houses, the seating allows all aboard finding private areas to enjoy the sailing or relax with a book. The pulpit has a large triangular seat from where the power of Adèle is really appreciated, looking aft at her 290 tonnes cut-ting through the seas.

There is a second owners’ cockpit aft, with two large armchairs facing diagonally aft and a big half-round sofa looking forward. We often took our drinks in that cockpit with our guests before dinner in the main cockpit. And if there were only a few guests aboard we sometimes had dinner aft as well. Aft of this cockpit is another relaxation area for sunbathing or catching the occasional fish with our rods!

Interior

The main deck house is the major interior social centre, with the dining table to port, opposite low sofas to starboard, and navigation and communication equipment at two desks forward. There are two sepa-rate computers, which both have a complete chart system. One is used for immediate control, with a repeater on deck. The other system, on the port side, is used for planning our passages. We can analyse a course and look into a possible harbour for the night without interfering with the system with which the watch is navigating Adèle through the immediate obstacles. The computers are able to communicate with each other and a new route can be transferred from the planning to the navigation/control computer.

Also to starboard, and half a level down from the main deck house is the captain’s office, where there is a third computer for communication and weather forecasting. Beyond that is the control room with access to the engine room.

Descending forward from the main deck house is the main saloon and the library, which also served as my office, where I kept in contact with the outside world, wrote this book and edited the photos. To port in the saloon is a plasma screen for watching tv or dvds, or even the chart. To starboard is a wood-burning fireplace in front of two sofas and two more armchairs.

Forward of the saloon on the port side are two guest cabins and aft of the deck house are two further guest cabins, four in all.

Forward of the forward guest cabins you enter the domain of the crew – the galley, the crew mess, four crew cabins, each with its head and shower, and the laundry room, always busy with a contingent of around 18 people present on many of our voyages.

Going aft past the two aft guest cabins, you enter the owner’s suite, where Jennifer and I not only had a bedroom with a sofa and a writing desk but also a bathroom with Jacuzzi, a dressing room and a private sitting room in the aft deck house with sofas, bar, a writing desk for Jennifer and a plasma screen.

But Adèle has three deck houses – the third is forward, with a little sitting area accessible from the forward guest cabins or the crew area. Sometimes appreciated by guests who wanted to withdraw and still watch what was going on, it was mainly used by the crew as a social area, especially in heavy weather. Many times I found my Jennifer playing scrabble with Georgina, our bosun, in that deckhouse, or saw Claire, our chef, getting a well-deserved nap in rough weather.